I was terribly sad to learn last night that my Facebook friend, Les Reed had passed away. Even at 83, he seemed full of limitless energy and was never less that robustly ebullient. There was never the slightest question that he had lived his life to the full and loved every adventure along the way. He shared stories of incredible talents he worked with by always giving credit to them first and foremost, despite his often pivotal role in their careers. He had an old-school level of politeness that meant that when he wished you ‘happy birthday’, it felt like he actually meant it and you felt obliged to do as instructed. In every way – they don’t make ’em like Les anymore.

Leslie David Reed OBE was born on 24 July 1935, in Woking, Surrey. Having learned to play the piano from the age of six, it was an instrument he stuck with, rising through the grades until he ultimately graduated from the London College of Music. He was always a willing performer and, as we all did, plastered his walls with his musical heroes, from Glenn Miller to Sammy Davis Jr. The difference between Les’ life and ours is that the heroes of his wall would eventually become musical partners and friends.

After leaving school, Les took the traditional route of any jobbing musician, playing with his trio at weddings, dances and working men’s clubs, until War intervened. This period too was productive for Les, learning both the clarinet from the leader of the army band and gaining experience in musical arrangement – still the lost and forgotten art of the composer. Gigs at Butlins saw him appearing on the same bills as The Drifters and Cliff and The Shadows, before a meeting with Barry Mason and John Barry in 1959 led to a period of Les’ life where he feet barely touched the ground.

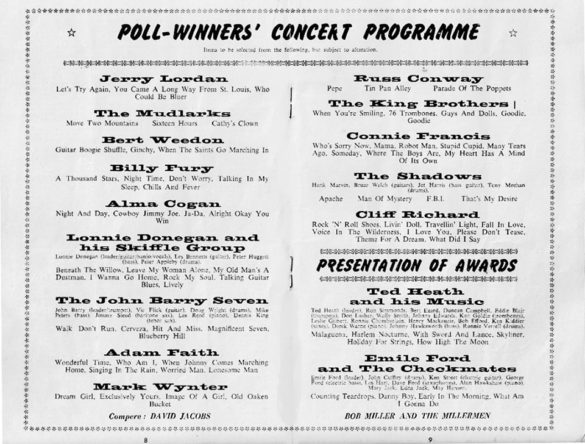

Eager to recruit a pianist for his group, John Barry auditioned Les (successfully) for The John Barry Seven, a period in which the band appeared on Drumbeat, the BBC’s top youth music show, as well as what would cap off any other musician’s career, performing on the immortal James Bond theme, initially for Dr No, released in 1961, ultimately, seemingly, for the rest of time. His period playing alongside Barry was brief, Les seeing his ultimate calling being as a conductor and arranger.

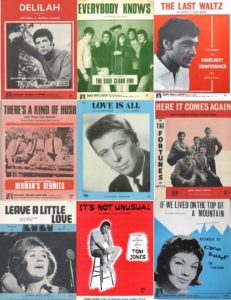

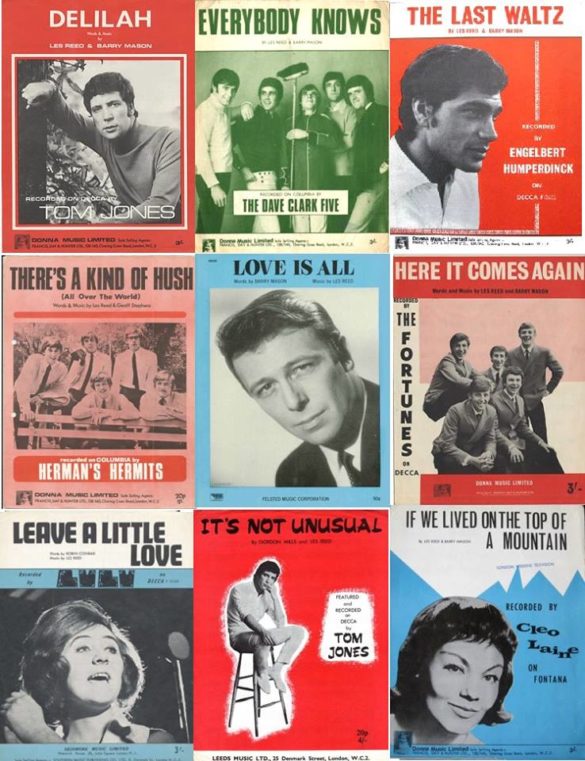

His first jobs were at Pye Piccadilly, working, successfully, with Joe Brown but a casual trip down London’s Denmark Street (at the time and today to a much lesser extent, the heart of the UK’s music songwriting talent) saw him meeting songwriter, Tony Hiller, the cue for Les to turn his hand to hit creation. Spoiler alert – he became quite good at it. Les worked alongside a succession of lyricists, starting with Geoff Stephens, who between them scored hits with The Applejacks (“Tell Me When”); The Fortunes’ “here it Comes Again”; Lulu’s “Leave a Little Love” and Herman’s Hermit’s “There’s a Kind of Hush”.

In 1965, Les was summoned to watch an act at a cinema in Slough who it was thought had potential. Les was less than impressed with the tight leather trousers and frilly shirt than he was with the ear-popping voice when he opened his mouth to sing. This unknown upstart – Tommy Woodward – would soon become Tom Jones and Les as his secret weapon…and what a weapon – welcome everyone to: “It’s Not Unusual”; “Delilah”; Daughter of Darkness”; “I’m Coming Home” and “Green, Green Grass of Home” (the co-production, arranger and pianist, if not the writer in this case).

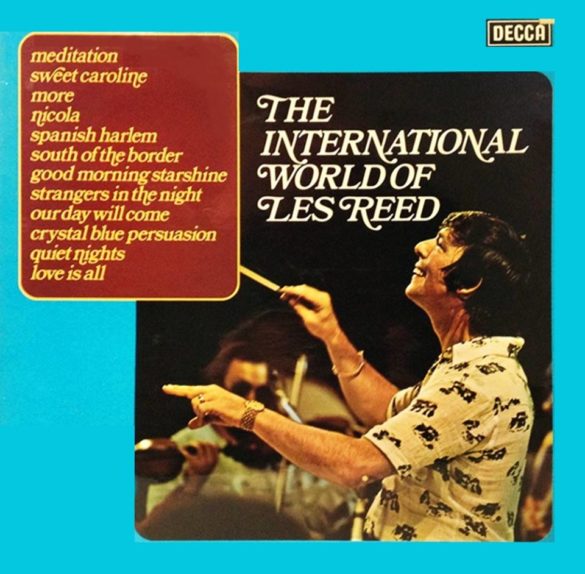

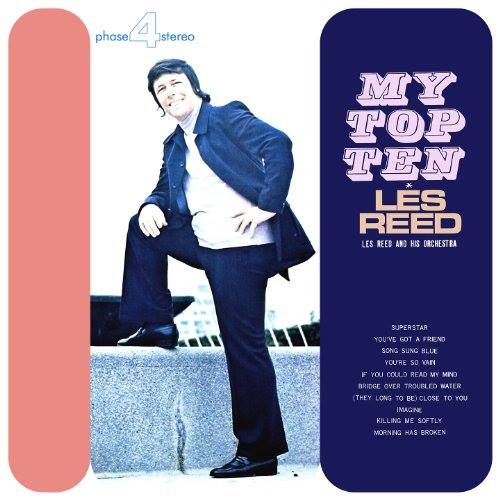

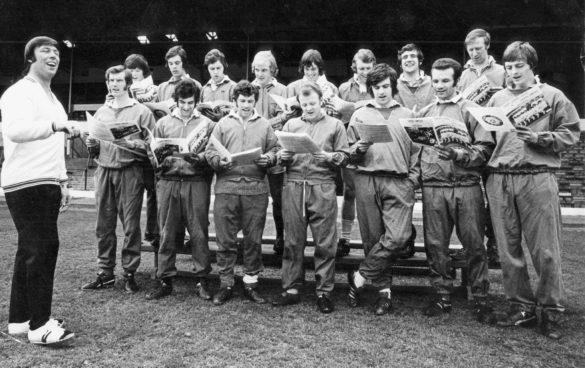

From here, there was an avalanche of hits for so many stars: Engelbert Humperdinck’s “Last Waltz”; hits for the Dave Clark Five, Petula Clark, Des O’Connor, Elvis, Shirley Bassey, Leeds United’s “Marching on Together (Leeds, Leeds, Leeds)”, Connie Francis…Allmusic notes that “Reed’s sixty or more major hits have earned numerous gold discs, Ivor Novello Awards and, in 1982, the British Academy Gold Badge of Merit. In the mid-1960s, it was unusual for a British singles chart not to list a Les Reed song”.

Also of great note was the work Les Reed did for television and film. His immediately recognisable theme, “Man of Action”, was used for radio for many years. He was also to score two films which stand out today as films which capture the 1960s in an incredibly evocative way: “Les Bicyclettes de Belsize” and “Girl on a Motorcycle”. The former, Douglas Hickox’s all but dialogue-free short film gave Engelbert another chart-botherer, whilst the latter is a milestone in 60s style, Jack Cardiff’s stylish drama starring Alain Delon and Marianne Faithfull. Les and I spoke about reissuing Girl on a Motorcycle but sadly, as usual, the rights were impossibly tied up. It was good to chat about it anyway. Other works for film include his theme to 1979’s “The Lady Vanishes”, the score to, thrillingly, the “George and Mildred” movie, plus “Broken Love”; “Street Kid”; “My Mother’s Lovers” and, oddly, “Creepshow 2” alongside Rick Wakeman. His final work for film was also that of its director – Michael Winner’s “Parting Shots”.

Alongside a raft of awards, from Ivor Novello’s to the Freedom of the City of London to his OBE in 1998, Les remained humble and grateful, his death yesterday leading to tributes from Tom Jones, Mike Batt, Sir Tim Rice and Connie Francis, who said the following:

“I cannot begin to tell you how saddened I am by the loss of my dear friend, Les Reed.

Les gave new meaning to the word “gentleman”. He was an outstanding musician and composer. I loved working with this wonderful man. Recording the “Songs of Les Reed” was one of the highlights of my life. Godspeed Les, you will always live in my heart”.

Daz Lawrence